Courtesy: Prabuddha Bharata

THE IMPORTANCE OF the role of the mind in human life cannot be exaggerated. It is so important that Yogavashishtha asserts: ‘Mānasam viddhi mānavam; human is indeed mind only’1. It further says:

The mind is all (I.e. the agent of all actions): therefore, it is, that by the healing of your heart and mind, you can cure all the troubles and diseases, you may incur in the world.2

One can go on quoting any number of statements related to this subject. A human being plays different roles in different situations and behaves differently in different places and with different people, being induced by different states of the mind just like the electric bulbs with changing colours.

Ancient Greeks identified three important faculties of the mind: thinking, feeling, and willing. These can be translated into Sanskrit respectively asālochanā śakti, bhāvanā śakti, and icchā śakti.

Thinking Faculty (Ālochanā Śakti)

‘This is related to different thoughts, either good or bad, arising in our minds when we see or hear or think about a person or an object or an event. And most of these thoughts are repetitive and useless, and as a result, a good deal of our mental energy gets drained out. To prevent this, we have to channelise our thoughts in a definite direction and give them a concrete form. This process is called conceptualisation—giving our thoughts a definite conceptual form. We form a definite idea of a person as to his nature, personality, and the like, by observing his actions, speech, behaviour, and thinking about them carefully with the phenomenological approach. Similar is the case with different objects or events. This thinking faculty, when properly channelised, gives rise to different forms of knowledge and in this way, we acquire an enormous fund of knowledge in the field of science, philosophy, and allied subjects. And this capacity of conceptualisation has made human a unique creature, distinguishing from other animals.

Edward De Bono explains with an appropriate example of how thoughts get channelised:

A landscape is a memory surface. The contours of the surface offer an accumulated memory trace of the water that has fallen upon it. The rainfall forms little rivulets which combine into streams and then into rivers. Once the pattern of drainage has been formed then it tends to become ever more permanent since the rain is collected into the drainage and channels and tends to make them deeper. It is the rainfall that is doing the sculpting and it is the response of the surface to the rainfall that is organizing how the rainfall will do it sculpting.

We read newspapers every day. As a result, we come to certain conclusions regarding the current political or social conditions of our nation depending upon our power of thinking and cultural as well as educational background. This is the result of our thinking faculty.

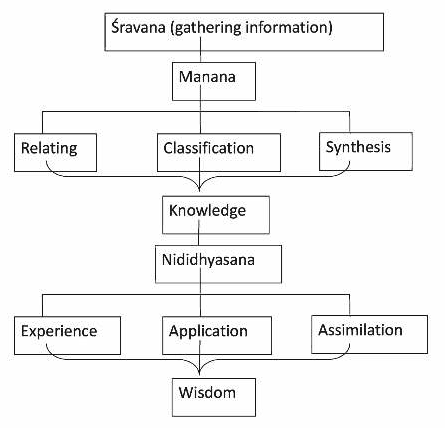

In our scriptures, we come across the concepts of śravana, manana, and nididhyāsana, and these are the three stages of sadhana in Advaita Vedanta. These can also be interpreted as three stages of transformation of information into wisdom. Here śravana means hearing or gathering of information. That mere gathering of information is not knowledge is an undisputed opinion of all great thinkers of all time. The information has to get morphed into a definite form of knowledge, through the process of conceptualisation. This process is called manana, which involves three factors: relating, classifying, and synthesising.

Firstly, we have to find out the relation between different bits of information. For example, making a comparative study of Vedanta and science or relating Vedantic thoughts with the discoveries of modern science. Similarly, we make a comparative study of religion, relating apparently divergent concepts of different religions. Through this process, the unrelated information will get crystallised into a definite form of knowledge.

The second step is classification. In a library,they classify the books according to their content. In the like manner, information also is to be classified as to which category they belong to, whether to religion, philosophy, science, sociology, and so on. Through this process of classification which is based on good understanding and deep thinking, the information will get chiselled into a definite form of knowledge. Otherwise, all the information will get muddled up leading to confusion and conflicts. It is a well-known fact that considering the caste system in India, a social issue, as a part of religion, has led to so much misunderstanding in Hinduism, and hindered social development.

The next step is synthesis, which refers to synthesising the different related information and arriving at new conclusions or sculpting a new way of thinking. Through this process, different branches of knowledge emerge, and thousands of books and articles are written and published, and new discoveries and inventions are made in science and new theories of philosophy are formulated. This is how the horizon of human knowledge is ever-expanding.

The process of converting the raw information into a definite form of knowledge through the mental act of relating, classifying, and synthesising can be called manana. It is something like preparing nice dishes in the kitchen mixing different spices and vegetables following a certain recipe.

After preparing some tasty food, it is unwise not to eat it. One has to swallow and digest it;and it has to become a part of our system. Similarly, the knowledge that we acquire through manana has to become an inseparable part of our personality system, giving a positive direction to our personality. And this becomes possible through nididhyāsana, in which three factors are to be considered: experience, application, and assimilation.

We undergo different kinds of experiences in the form of happiness, misery, and the like in our life. Many live a mechanical life as though they have forgotten the art of experiencing life. There is a world of difference between ordinary sense perception and experience. Animals just see a flower ,whereas a human can experience the beauty of the flower. What is just a ‘sound’ for animals can be melodious ‘music’ for a human being. People eat their meals mechanically as a daily routine, except a few who experience the taste of it. For the majority of people, work is drudgery and they do not derive any satisfaction from it. However, there are an enlightened few who derive a sense of fulfilment from the work; and for them, it is an experience. If the knowledge that we acquire is integrated with our life experience, then it becomes our own; and life becomes enriched. When different colours are aesthetically combined, a beautiful painting emerges. Similarly, when knowledge is fully assimilated into our personality system, a beautiful personality blossoms.

While reading The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna,if we apply the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna to our life experience, then they assume greater meaning and become a part of our personality system. In this way, enrichment of the personality takes place through the application of knowledge. Some people study scriptures with interest to become rich in knowledge, but not for the enrichment of their personality. They may be filled with knowledge, but not fulfilled in life. Sri Shankaracharya calls this tendency Śāstravāsana. Sri Vidyaranya says that there are three kinds of Śāstravāsana: Pāțhavyasana, Bahuśāstravāsana, and Anușțhānavyasana3 (vāsana means bad tendencies and vyasana means attachments, the results of bad tendencies). Some are only interested in memorising the different scriptural texts and reproducing them at ease (pāțhavyasana). Many scriptures and scriptural statements would be at the tip of their tongue. They evince no inclination in taking them into their brain, not to speak of taking them into their heart. And there are others who are interested in acquiring an enormous wealth of different areas of knowledge and being recognised as ‘moving encyclopedia’(bahuśāstravāsana). Still, there are others who are interested only in observing rituals spoken of in the scriptures, as if they suffer from ritual addiction (anușțhānavyasana). There are some people who are above these categories and live a life of fulfilment absorbing and adopting the essence of the scriptures in their life.

Through experience and adoption, knowledge becomes one with our life and gets reflected through our actions and behaviour. In the words of Swami Vivekananda, this can be called ‘Nervous association of certain ideas’, and in this context, this process might be termed as Nididhyāsana. The whole process of transformation of information into wisdom is depicted in the chart (see the following flowchart).

This process of information getting transformed into a crystallised form of knowledge and then shining forth as wisdom is called the sublimation of ālochanā śakti.

Faculty of Feeling (Bhāvanā Śakti)

The transformation of negative emotions into positive ones can be considered as the sublimation of bhāvanā śakti. Emotion is very powerful, and it is this that gives muscle to the thinking faculty. Swamiji’s thoughts are so powerful because of the strong feeling for humanity behind them. A soldier may be physically very strong, intelligent and might have undergone excellent military training. Still, what is inevitably required for him to fight in the battlefield most valiantly is the zealous feeling fired by his love for the country. Even the most weakling and timid can dare to attack others if he is seething with anger. Emotion is like petrol to a vehicle; the body of the vehicle may be very good; the engine may be absolutely perfect; the driver may be excellent; but still, the vehicle cannot run without petrol.

Generally, the power of emotion exudes itself in the negative form as lust, hatred, anger, fear, and the like. Turning the same power to a higher direction is called the sublimation of emotion. According to anthropologists, the development of culture in a particular tribe is proportional to the suppression of the sexual energy of man.They found the greater cultural development in such a tribe where there is a greater control of the sexual drive. As we refine the crude oil in a graded manner, or as we divert the water of a river for constructing a dam across it, so also our crude emotions or animal propensities are to be sublimated stage by stage, till they will emerge as a great spiritual force. This mental energy, which initially is creative at a lower level, is to be made active at a higher level. At the first stage, it is to be converted to the form of positive feelings like love,kindness, and so on, developing good human relations through them. This psychic energy will be transformed into a positive force through creative activities also. Further still, it will burst forth as a strong spiritual aspiration.

In this context, we can consider certain methods of the sublimation of psychic energy:

1. Dispassionate Action (Karma Yoga)

We have to consider work as a necessity for both physical and mental health. In an ordinary sense, work is meant for getting something- to acquire wealth, to possess power-position, or to enjoy desired objects of senses, or just earn a livelihood. These kinds of work cause bondage, and to get free from this bondage is the ultimate goal of man. In the traditional view—first, there is ignorance (avidyā), which gives rise to desire (kāma), and this, in turn, induces to act (karma) to fulfil those desires. The fulfilment of a desire engenders more desires and as a result, work also increases. And in the course of time, we get enmeshed in the web of ever-increasing activities. This attitude towards karma is to be changed.

The work is not meant for gaining something from outside, rather to bring out something from inside. We have to accept activities as a means of unfolding our inner potentialities like talents and capacities; love and compassion; strength and goodness and the like. The manifestation of these can be possible only through conscious activities, without which all these remain latent—rendering the human personality underdeveloped. Development is always a process of manifestation of potentialities from within. There is a saying in English that beautifully expresses this idea: ‘When the egg is broken from an external force, life ends; and when it is broken from internal force, life begins.’ So we have to accept karma or action as a means of our all-round development, not as a burden or bondage. Hence the direct result of work becomes secondary.

Abstaining from work with some pretext or laziness is unhealthy, especially in the mental realm. It is the productive work that gives some meaning and worthwhileness to our life, and the lack of which leads to depression—the mental disease which is widespread among people of all ages nowadays. It is worth quoting Alexis Carrel regarding laziness:

Laziness is particularly lethal. Laziness does not only consist in doing nothing, in working badly or not at all, but also in devoting one’s leisure to stupid useless things. Card-playing, cinema,radio, endless chatting, rushing about aimlessly in motor-cars—all these reduce intelligence. It is also dangerous to have a smattering too many subjects without acquiring a real knowledge of anyone. We need to defend ourselves against temptations provided by rapidity of communication by the increasing number of magazines and newspapers, by the motorcar, the airplane and the telephone, to multiply to excess the number of ideas, feelings, things and people which enter into our daily lives.4

It is obvious to all now that a number of avenues are open to us to boost up laziness and spending our time aimlessly and uselessly, thanks to the spectacular advancement in communication system and information technology. Earlier the great problem was how to spend time without work, and now the problem is how to get some time to do something worthwhile. Present social media, being indiscriminately used, is insidiously cutting the silken threads of all human relationships, lending them vulnerable to all kinds of mental maladies. It is because mental health primarily depends upon symbiotic relationships.

Even though Sri Krishna said in the Bhagavadgita that lust and anger are the products of rajas (unduly active or restless nature); ultimately they sprout luxuriantly as seeds in the fertile field of tamas (dull ignorant nature) that produces laziness and lethargy. A lazy person has no place even in hell, says Swamiji. Secondly, we have to accept work from a social standpoint, considering it as a service to society. Every work can be a service to society. A trader doing his work for his own profit is rendering a service to society; perhaps, unintentionally. Many people would be benefitted from using the products produced by a profit-making industry. Suppose a person is running an industry or a business without the idea of personal profit as the only motive. He or she derives the sense of inner fulfilment as a result of rendering service to the society through that industry or business. Otherwise, if the vision is restricted to his or her personal profit only, regardless of social concem, then the resulted contraction of consciousness will cause mental and nervous tension, the results of which are obvious to all. If the work is done with the awareness that every work has its own social dimension, its own effect on society, and no work is purely personal—such work is socially fulfilling and personally elevating.

Thirdly, doing work with a spiritual attitude. And this again has two dimensions depending upon whether the spiritual aspirant is knowledge-oriented (jnani) or devotion-oriented (bhakta). The Jnani will do all the work with the conviction in the mind that Prakriti or Nature is doing everything since body, mind, and senses are products of Prakriti. The Self is actionless and hence both work and its results belong to Prakriti and not to the real Self. It cannot be said that a person is ‘doing’; it just happens. Bhakta, on the other hand, performs all activities with the fervent attitude that all work with their results belongs to God, he being just an instrument in His hand.

The whole universe is a cosmic sacrifice (vishwayajna) and every bit of activity is a part of cosmic sacrifice, and God is the Lord of the sacrifice (yajnapurusha). Naturally, all activities belong to Him; we have no claim over it. No part of the body in this human personality works for its own sake; the functions of all parts belong to the whole personality system. Similarly, all our works belong to the whole universal system. With this holistic attitude, the work, and along with that, the psychic energy also will get sublimated. In this way, the psychic energy hierarchically gets expressed at a higher level; first as manifestations of inner strength and capabilities, and secondly as social concern and responsibilities, and finally, as spiritual aspiration.

Two persons go to the same office to work. One among them with great enthusiasm collects all the information related to his work; studies with avid interest all the related things pertaining to the work on hand; contributes his might to do that job to the best of his capacity, and as a result, derives satisfaction from it. Another one, on the other hand, pins his attention to finish his job somehow not incurring the displeasure of others and get out of the office. Many people merely work; they do not accomplish anything. Most sweepers only sweep, but do not clean the ground. For such people, work and even life are a great burden. Swami Yatishwarananda says:

Do not do your duties in a haphazard way. If we meditate properly, we can work properly. Work and meditation are inter-related. Do everything in life with as much care as possible. Nothing is too low for us and nothing is too high. If we work fora good cause sincerely, we feel uplifted, we feel great peace and joy. Sometimes we progress in spiritual life more through service than through meditation. If we are easy going in work, we shall be easy going in meditation also.5

2. Creative Activities

Aesthetic sense and art experience are also special characteristics of human beings, like conceptualisation as explained earlier. Bhartrihari says: ‘Sangīta-sāhitya-kalā-vihīnah sāksāt pasupuccha-visāna-hīnah; the one who does not have appetite for music, literature, or art, is indeed an animal without tail or horn.’6 It is not that everyone should become a musician or a writer or an artist. What is important is being endowed with the capacity of relishing and appreciating, not being insensitive to the artistic expressions. And this aesthetic sensitivity helps one to reach a higher emotional level, preventing the mind from being creative at the lower level. It also helps in getting relieved from mental and nervous tensions.

Moreover, creativity is not restricted to different branches of art like music or literature alone. Creativity can be expressed in any field of activity. In agriculture, it can be expressed in the form of making new experiments in cultivation. In technology, there is innumerable scope for new experiments. So is the case in all other activities. However, what is important is the mind free from self-seeking disposition, which deadens all creativity. The work savoured by creativity gives a greater sense of fulfilment and inner satisfaction. As human beings, we must aspire to get happiness from the sense of fulfilment rather than through sense gratification. The person who derives satisfaction in one’s own field of work will not try to avoid work as boredom and try to seek happiness outside the field of work, demanding more and more leisure hours and reducing the working hours. One who is dissatisfied with the work spends time idly during the leisure hours. As a result, work suffers and one will have grievous mental suffering.

We have to consider one important fact regarding the taste for art. If there is a lack of spiritual aspiration or other higher ideals, then artistic talents may make one sensuous. We see many great artists, musicians, or writers intensely sensuous. Girish Chandra Ghosh was a great genius and equally sensuous; while Swamiji, though a great versatile personality, never turned to sense objects because of his intense spiritual aspiration.

American psychologist Abraham H Maslow classifies creativity into three categories: primary, secondary, and integrated. The primary creativity is related to different kinds of talents that are inborn, not cultivated later, like child prodigies. It is quite possible that many people may have inborn talents and capacities which are suppressed due to want of effort or pressure of circumstances. Secondary creativity is cultivated with effort, imbibing the ideas and works of others, and learning from others. Maslow says:

This later type includes a large proportion of production-in-the-world, the brigades, the houses, the new automobiles, even many scientific experiments and much literary works. All of these are essentially the consolidation and development of other people’s ideas. ... The creativity which uses both types of process easily and well, in good fusion or in good succession, I shall call ‘integrated creativity’. It is from this kind that comes the great work or art, of philosophy or science.7

3. Intellectual Study

The disciplined and systematic study also contributes much to the sublimation of emotional power. It is already discussed under the title ‘Thinking Faculty’. In this connection, what we have to remember is that a mere gathering of information, which can be considered as ‘studying’, makes the mind more restless, and consequently, the negative thoughts and emotions may dominate the mind. Not only that, it becomes an obstacle to spiritual practice. Herbert Simon, a Nobel Prize winner in economics says: “Hence a wealth of information creates poverty of attention’. Jeremy Rifkin says:

Strangely enough, it seems that the more information that is made available to us, the less well informed we become. Decisions become harder to make, and our world appears more confusing than ever. Psychologists refer to this state of affairs as ‘information overload’, a neat clinical phrase behind which sits entropy law. As more and more information is beamed at us, less and less of it can be absorbed, retained and exploited. The rest accumulates as dissipated energy or waste. The build-up of dissipated energy is really just social pollution and it takes its toll in the increase in mental disorders of all kinds, just as physical waste eats away at our physical well-being.8

To be recognised as a popular speaker, it would be enough if one possesses eloquence and a good amount of information. The people who are addicted to popularity, will not feel inclined to make a deep study and serious thinking of any subject, which are necessary to write a good original article or a book. Even if they write something, it is only a collection of some information from the internet. For sublimation of psychic energy, deep thinking and study are necessary, avoiding intellectual lethargy.

4. Pratipakșabhāvanā

This concept is familiar to the students of the Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali. He says in an aphorism: ‘Vitarka-bādbane Pratipakșa-bhāvanam; when bad thoughts arise in the mind, we have to think their opposites.’9 Thoughts of violence are to be controlled by bringing in the ideas of non-violence; thoughts of hatred are to be suppressed with the thoughts of love and affection. Similarly, with other bad thoughts. We have to tell our minds strongly that negative thoughts are harmful to us both physically and mentally, and they erode human relationships by creating a vicious atmosphere around us. We have to go on increasing the samskaras of positive good thoughts so that these good samskaras will fight and nullify the negative bad samskaras. Through incisive analysis, we have to find out the exact opposite of any unwholesome thought that arises in the mind. For example, being jealous of somebody else’s fame or popularity may not be due to hatred towards that person as Duryodhana had for Pandavas; rather it could be because of an inordinate desire for name and fame. In this case, thoughts of love may not help; along with that, one has to overcome the desire for name and fame, impressing the mind of its shallowness and diverting one’s attention to a higher spiritual ideal.

An experiment in neurology shows how this Pratipakșa-bhāvanā helps us in overcoming a habit by making a structural change in the brain. David Eagleman in his book The Brain10 speaks about this experiment. Though the word Pratipakșa-bhāvanā is not mentioned there, the concept is very similar. A woman called Karen was addicted to the drug called crack cocaine, for over two decades, and she was almost ruined by that drug. She sincerely wanted to be free from it, but was trying in vain to do so. In that experiment, she was put into the brain scanner called fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). She was shown the picture of crack cocaine. Soon, there was an upsurge of craving for that drug which activated a particular region of her brain that can be ‘summarised as craving network’. Now she was asked to think of counter thoughts to the craving, such as how that drug was ruining her life, disturbing her mental balance, rupturing family relations, and disrupting her career. These thoughts activated a different set of brain areas which was ‘summarised as the suppression network’. The battle between these two went on for some time, and ultimately craving network was disarmed by the suppression one. She was seeing the whole warfare that was taking place in the brain on a computer screen. This direct observation of the effect of the practice boosted her confidence and eventually, she was able to be free herself from the bondage of addiction. It is interesting to note here how Pratipakșa-bhāvanā can transform human personality through neurosculpting.

As related to Pratipakșa-bhāvanā, we may also refer to the rational approach to emotional situations. When others act against us, criticise us, or hurt our feeling through their behaviour or words, negative reactions trigger in our minds. This fire of negative reactions can be doused or its intensity can be minimised through rational thinking, looking at the adversary situation from a totally different angle. For example, if we come to know that someone whom we loved and helped is criticising us, then immediately we may get incensed; and many negative thoughts start bubbling up in the mind regarding that person. However, holding on to ourselves, we can start thinking that the criticism might be a false report; or it might be a conspiracy to sour our relationship; or what the person spoke about me might have been wrongly understood. We may even think philosophically that criticism need not be taken so seriously as in no way it is going to harm us. Through this kind of thinking, negative reactions can be controlled. Only, we have to apply this to various situations in different ways.

5. Forgiveness

We have to forgive others’ mistakes not for their good, but for our own good. Fred Luskin in his book Forgive for Good says: ‘Holding on to hurts and nursing grudges wear you down physically and emotionally. Forgiving someone can be a powerful antidote.’11 An experiment was conducted in Michigan, USA with 71 people. When they were made to remember old, painful, and harmful feelings and their physiological reactions were measured through a sophisticated machine, their blood pressure, heartbeat, and muscular tension increased.

Then they were asked to think of love, sympathy, empathy, and all the positive feelings; and as a result, the negative reactions subsided, and their blood pressure became normal. The conclusion is that negative feelings like hatred, holding grudges, and so on produce a deleterious effect mentally, physically, and emotionally.

Normally in a family, or any institution or society, it is not possible to remain unhurt; intentionally or otherwise people hurt us and we too hurt others. We must accept that we are also equally capable of hurting others. So it is not possible to live in a society without hurting each other, and it is good for us to accept this reality candidly. Since we expect others to forgive us for our wrongs, we too should forgive others. We must have the humility to accept our mistakes and develop magnanimity to forgive others. Forgiveness does not mean not punishing others for their mistakes, but it actually means not to entertain any grudge or ill-feeling towards the ones who hurt or harm us. If we harbour such feelings, it amounts to punishing ourselves for other’s mistakes. Such negative and hurtful feelings will get ballooned as we brood over them. ‘We must avoid this through the attitude of forgiveness, and sympathising with the one who hurt us, because, no one deliberately hurts others unless he is already hurt within himself.

The expansion of heart and mind takes place through the attitude of forgiveness, and this expansion will prevent many little things that disturb our inner being. As Sri Ramakrishna says, if an elephant rushes into a small pond, there would be a lot of commotion of water; and if the same elephant enters into a big lake, the water will remain calm and unruffled.

6. Prayer

Through forgiveness, we have to check inner reactions and through prayer, that power is to be directed towards God.Through intense prayer, the power working at the lower level will rise to a higher level, and it will be transformed into bhakti, loving devotion. The importance of prayer lies not in answering of prayer, but in the gradual transformation of the personality.

Swami Yatishwarananda says: ‘It is therefore only good that so many of their selfish worldly prayers are not “answered” at all. If God were to fulfill every wish of everybody, the world will be in chaos and every surviving man will be mad’.12 ‘When God wants to punish us, He will answer all our prayers’, says Oscar Wilde.13

As we progress spiritually, spiritual needs become more predominant, rendering physical and psychological needs inconsequential or irrelevant. When the aspirant feels spiritual needs strongly, then his or her heart pours out in the form of prayer. When the external needs lose their importance, one can steel oneself against the upsetting events and persons.

The real answering of prayer is beautifully explained in the following words: ‘If any prayer becomes so concentrated that it thrills every particle of your life, stirs your heart to throbbing, affects your dreaming in the night, envelops your daydreams, infiltrates your sleep and becomes the obsession of your life, then the prayer is answered.’ We have to pray for others as well, even for those who hurt us, to guard ourselves against negative reactions. Prayer is a good antidote to heal the hurt feeling within us.

Icchāśakti or Will Power

The sublimation of will power is to be achieved by freeing it from the clutches of desires. Normally the will is one with the desires. That is to say, when any desire arises, the will unidentifiably becomes one with it to such an extent that we seldom realise that we have a will power that is separate from desires.In the majority of people, the strong desire itself acts as will power. Such a will power is called avyavasāyātmikā buddhi by Sri Krishna in Bhagavadgita; since it is under the grip of desires, which are innumerable, it has many branches. In contrast to this,vyavasāyātmikā buddhi, one-pointed willpower is always focused on one ideal.

As the willpower is extricated from the grip of desires, it is drawn towards the Atman, and shines in the spiritual light of the Atman. And now the ‘will’ can be called ‘enlightened intelligence’. Freeing the ‘will’ from the desires and turning it towards Atman—this process can be termed as sublimation of will.

This ‘will’ is to be strengthened by applying it on every occasion with determination. One must apply it assertively with a ‘yes or ‘no’ even in not so consequential matters; and, of course, follow that resolve. The firm resolve will influence and direct our actions, whether it is good or bad. When we perform any religious ritual, we start with a resolve (sankalpa) which means, we resolve to complete it successfully with a firm determination. Similarly, in other activities also, we have to start them with a firm resolve, and this will obviously change the quality of our action. For example, when we sit to study something we must resolve: ‘I will not budge from this seat for an hour or so till I fully understand this subject’. This kind of sankalpa will make the mind more concentrated and as a result, we understand the subject better. While sitting for meditation, if we resolve not to allow any other thought unrelated to the object of meditation, the quality of our meditation will surely improve.

When desires, temptations, lust, anger, and the like are controlled by the willpower, the resulting conservation of energy is called character strength. When we have to rescue the drowning man and drag him to the shore, we have to be firmly anchored on the ground by holding a pillar or tree or something firmly fixed. Otherwise, we will also get drowned. Similarly, the ‘will’ is to be firmly anchored in God to control the desires; other wise, it will also get drowned in the strong current of desires. An unrelenting struggle is required for the ‘will’ to have sway over the impetuous desires.

If we continuously fail to act according to our resolve, in course of time, we don’t feel inclined to resolve at all, and become easy prey to all mental vagaries. For example, some people resolve every day to get up early in the morning but fail to do so. Such people cannot achieve anything in life.

The mental energy that goes rushing down-ward is to be checked with the help of a dam called self-control, and it should be raised to a higher level with the help of a pump called higher ideal, and make it work at the higher level. This long assiduous process is called the sublimation of psychic energy.

References

1. Yoga Vashishtha, 3.115.2.4.

2. Ibid., 4.4.5.

3. Swami Vidyaranya, Jivan Mukti Viveka,trans. Swami Mokshadananda (Kolkata: Advaita Ashram, 2010), 120.

4. Alexis Carrel, Reflections on Life (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1953), 117.

5. Swami Yatiswarananda, Meditation and Spiritual Life (Kolkata: Advaita Ashram, 2013), 668.

6. Bhartrihari, Neeti Shatakam, 12.

7. Abraham H Maslow, Towards the Psychology of Being (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold), 144.

8. Jeremy Rifkin, Entropy: Into the Greenhouse World (New York: Bantam Books, 1981), 170.

9. Patanjali Yoga Sutra, 2.33.

10. David Eagleman, The Brain (London: Canongate, 2016), 140-41.

11. Dr. Fred Luskin, Forgive for Good (US: Harper SanFrancisco, 2002).

12. Meditation and Spiritual Life, 361.

13. The Works of Oscar Wilde (London: Collins, 1923), 491.